In today’s complex and fast‑paced world, individuals, teams, and organizations constantly seek clarity on what they want to achieve and how to achieve it. This pursuit naturally leads to conversations about goals and objectives. Although these two terms are often used interchangeably, they are distinct concepts with unique functions and implications in planning, performance management, and strategic execution. Understanding the difference between goals and objectives is essential if you want to design effective plans and truly measure outcomes. This article offers a comprehensive examination of both terms, explores their practical relevance, highlights the nuances that set them apart, and provides actionable insights to help you apply these concepts in your personal and professional life.

In this article you’ll find: clear definitions of goals and objectives, an exploration of their characteristics, real‑world examples, a comparison of similarities and differences, common pitfalls, and best practices for setting meaningful goals and objectives that drive progress. By the end of this detailed and structured discussion, you will be equipped with the knowledge and tools to bring intentional focus to your planning processes.

What Are Goals?

Goals are broad, high‑level statements that articulate a desired end state or outcome. They provide direction and a sense of purpose. Goals answer the question, “What am I trying to accomplish?” and they often reflect long‑term aspirations. A goal can be personal, professional, organizational, or communal in nature. For example, a company’s goal might be to become the market leader in its industry; an individual’s goal might be to achieve a fulfilling work‑life balance.

Goals are inherently visionary. They help unify stakeholders around a common ambition and inspire action by offering a clear picture of what success looks like at a macro level. Because of their breadth and aspirational nature, goals do not typically detail the specific steps you must take to achieve them. Instead, they communicate direction and intention.

Characteristics of goals include:

They provide a general orientation. A goal sets the compass that guides your decisions and choices. For example, a nonprofit organization may have a goal to empower underprivileged youth through education. This goal does not specify how to accomplish empowerment or how to measure success; it simply states a broad aim.

They are usually long‑term. Goals tend to focus on outcomes that require time, sustained effort, and coordination across multiple activities. They may span months, years, or even decades. For example, a university may set a goal to become a top research institution within the next ten years.

They convey intrinsic motivation. Because goals are often connected to overarching values and purpose, achieving them can yield deep satisfaction and meaning for individuals or teams.

Goals often inspire momentum. When clearly articulated, goals can energize people and rally them around a shared mission or vision. They can serve as motivators during challenging moments and anchors during periods of uncertainty.

While goals are powerful in establishing intent and direction, they are not always directly measurable. That’s where objectives come into play.

What Are Objectives?

Objectives are precise, specific, and measurable outcomes that support the attainment of one or more goals. They detail what you will accomplish, how you will know when it’s achieved, and sometimes when it will be done. Objectives answer the question, “What needs to happen, and by when?”

In contrast to the broad nature of goals, objectives are grounded in specificity. For example, if your goal is to improve customer satisfaction, an objective might be to increase your company’s net promoter score by ten points within 12 months. This objective clearly delineates the target, metric, and timeframe.

Characteristics of objectives include:

They are concrete. Objectives specify exact results. They often contain quantifiable criteria so that progress and completion can be objectively assessed. For instance, a sales team might set an objective to increase monthly sales revenue by 15 percent over the next quarter.

They are short‑ to medium‑term. While objectives support longer–term goals, they typically focus on defined stages of progress that can be accomplished within a shorter cycle. This structure enables timely evaluation and necessary course corrections.

They lend themselves to accountability. Because objectives are measurable, they allow teams and individuals to track performance, compare outcomes, and hold themselves accountable for results.

They often follow the SMART framework. The SMART criteria—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time‑bound—are widely used to design effective objectives. A SMART objective enhances clarity and ensures it contributes meaningfully toward broader goals.

An objective might be to reduce employee turnover by 20 percent within six months or to publish 12 high‑quality blog posts within a quarter. These are definable milestones that can be evaluated for success.

How Goals and Objectives Work Together

Goals and objectives are not independent of one another. Rather, they are complementary. Goals define where you want to go, and objectives define how you get there. Objectives act as stepping stones toward realizing a goal. A goal without supporting objectives can feel abstract and difficult to execute, while objectives without a unifying goal can feel disjointed or directionless.

Imagine a large construction project. The goal might be to build a community center that serves local residents’ needs. Objectives might include completing architectural designs within three months, securing funding by the end of the year, finishing foundation work within the next six months, and completing interior work by a set deadline. Together, these objectives operationalize progress toward the overarching goal.

Together, goals and objectives provide structure to planning processes. Goals instill vision, objectives give form to action. Successfully combining both enhances clarity, focus, and performance.

Exploring the Difference Between Goals and Objectives

Understanding the difference between goals and objectives helps clarify expectations and improve execution. The gap between these two concepts lies primarily in specificity, measurability, timeline, and function.

Goals and objectives differ in the following ways:

Goals are vision‑oriented while objectives are action‑oriented. A goal communicates an aspiration; an objective lays out the concrete actions needed to realize that aspiration. A goal of “expanding market reach” becomes actionable only when paired with objectives like “enter three new regional markets within 18 months.”

Goals tend to be qualitative; objectives tend to be quantitative. A goal might describe a desired condition such as “enhancing brand reputation,” which is inherently qualitative. An objective would make it measurable, such as increasing positive customer reviews by 30 percent over the next year.

Goals span longer periods; objectives fit within shorter, defined periods. Think of goals as the destination on a map and objectives as the checkpoints along the route. The checkpoints help you verify whether you are on track.

Goals unify and inspire; objectives manage performance. A goal alone can motivate stakeholders by articulating a shared ambition. Objectives translate that ambition into manageable tasks that can be monitored and improved upon.

Goals often set priorities; objectives allocate resources. With a clear goal, organizations or individuals can decide where to focus energy and investments. Objectives then determine the specific allocation and sequencing of resources to ensure steady progress.

Once you grasp this distinction, it becomes easier to design plans that are both inspiring and actionable.

Why the Distinction Matters

In various contexts—business, education, personal development, government, and nonprofit sectors—the ability to differentiate between goals and objectives influences outcomes. When planning processes fail to distinguish these concepts, organizations can encounter confusion, inefficiency, and misalignment.

Consider a school district seeking to improve student performance. If it sets only a general goal like “raising educational standards,” educators may struggle to determine what success looks like or where to begin. However, when the goal is accompanied by clear objectives (such as improving standardized test scores by a specified percentage within a given timeframe), the strategy becomes actionable and measurable.

Without clear objectives, progress toward a goal can be hard to gauge. In team environments, people may interpret the goal differently, resulting in inconsistent efforts. Objectives establish shared expectations and create a common language for performance assessment.

The distinction also supports accountability. Leaders can assess whether actions align with strategic intentions by comparing outcomes with predefined objectives. This transparency enhances learning, fosters continuous improvement, and builds trust among stakeholders.

Understanding the difference between goals and objectives is not only a theoretical exercise but also a practical skill. It shapes how strategies are formulated, how teams operate, and how success is recognized.

Common Misconceptions

Despite the widespread use of the terms, several misconceptions persist:

One common misunderstanding is that goals and objectives are interchangeable. While both relate to desired outcomes, they serve different functions and require different levels of specificity.

Another misconception is that goals must always be quantifiable. In reality, goals often serve a qualitative purpose, providing inspiration and direction rather than numerical targets.

Some believe that objectives are rigid and inflexible. However, well‑designed objectives can adapt to changing conditions, especially when teams conduct regular reviews and are comfortable adjusting tactics.

There is also the belief that objectives without goals are sufficient for success. This is rarely true because objectives without a guiding vision can lead to fragmented efforts and missed opportunities.

Clarifying these misconceptions helps individuals and organizations design meaningful and effective plans.

Examples in Practice

To further illuminate the distinction, let’s explore examples from various domains:

In business, a company’s goal might be to enhance customer loyalty. Objectives supporting this goal could include increasing repeat purchase rates by 25 percent within a year and launching a personalized loyalty program by the next quarter.

In personal development, a person’s goal might be to become healthier. Objectives might include walking 10,000 steps daily, reducing sugar intake by half within three months, and scheduling annual health screenings.

In community development, a nonprofit may aim to reduce homelessness in a city. Objectives could detail increasing affordable housing units by a specific number within two years and securing partnerships with local employers to offer job training programs.

In education, a school’s goal may be to improve critical thinking skills among students. Objectives could include integrating problem‑based learning modules in every curriculum by the end of the school year and raising average critical thinking assessment scores by 15 percent.

Each of these examples demonstrates how goals set direction and how objectives break down that direction into measurable steps.

How to Write Effective Goals and Objectives

Creating effective goals and objectives requires thoughtful consideration and a systematic approach:

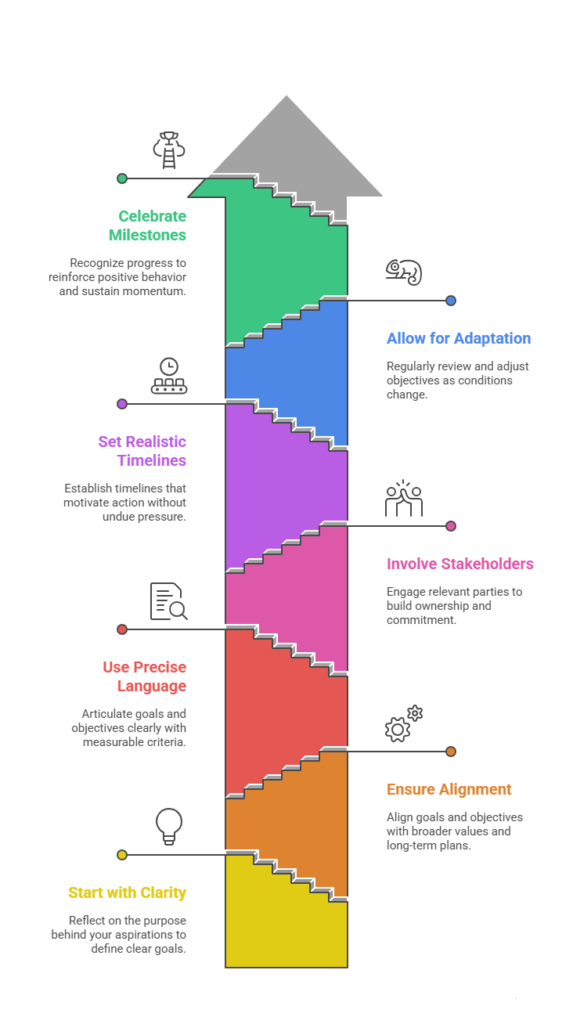

Start with clarity. Before you write anything down, reflect on the why behind your aspirations. What impact do you hope to achieve? Clear goals emerge from clarity of purpose.

Ensure alignment. Goals and objectives should align with broader values, mission statements, and long‑term plans. Misaligned objectives can lead to wasted effort and frustration.

Use precise language. Goals should be clearly articulated, and objectives should be written in a way that makes them easy to understand and track. Replace vague terms with measurable criteria wherever possible.

Involve stakeholders. Particularly in organizational settings, engaging relevant parties in the process of defining goals and objectives builds ownership and commitment.

Set realistic timelines. Objectives should stretch capacities without being unrealistic. Timelines should motivate action without inducing undue pressure.

Allow for adaptation. Conditions change, and strategies may require modification. Regularly review objectives and adjust as needed without losing sight of the overarching goal.

Celebrate milestones. Recognizing progress toward objectives reinforces positive behavior and sustains momentum toward long‑term goals.

Challenges and Solutions

Even with well‑defined goals and objectives, challenges can arise. Common hurdles include unclear expectations, lack of resources, shifting priorities, and resistance to change.

To address unclear expectations, revisit your language and ensure that terms are understood consistently across your team or organization.

When resources are limited, prioritize objectives that offer the greatest leverage toward achieving your goal.

For shifting priorities, maintain regular communication and be willing to refine planning documents. Prioritization sessions can help teams stay focused on what matters most.

To overcome resistance to change, create open channels for feedback and cultivate a culture that values learning and adaptation.

By acknowledging these challenges and proactively addressing them, you improve your chances of success.

Conclusion

In summary, goals and objectives are foundational elements of effective planning. Goals provide vision and direction, while objectives operationalize that vision into actionable and measurable steps. Understanding the difference between goals and objectives empowers individuals and organizations to craft better strategies, strengthen performance management, and achieve meaningful results.

By defining clear goals, articulating measurable objectives, and aligning both with your broader purpose, you set a course for success that is both inspiring and practical. Whether you are leading a multinational corporation, managing a community program, or setting personal targets, the ability to distinguish and leverage goals and objectives is indispensable.

With the concepts clarified and examples examined, you are now well‑positioned to evaluate your planning processes, refine your strategies, and advance toward your aspirations with confidence and clarity.